The (im) possibilities of artificial intelligence in education

17-4-2019

Commissioned by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, Dialogic investigated the impact that the use of artificial intelligence can have on education in the Netherlands. The aim of the research is to gain insight into how artificial intelligence is currently being used in education (and how it will be used) (what is the potential?), And what legal aspects play a role in that use (what is allowed?). The research must also expose the five biggest risks and opportunities associated with ths use (what do we want?).

The possibilities: what are relevant applications of AI in education?

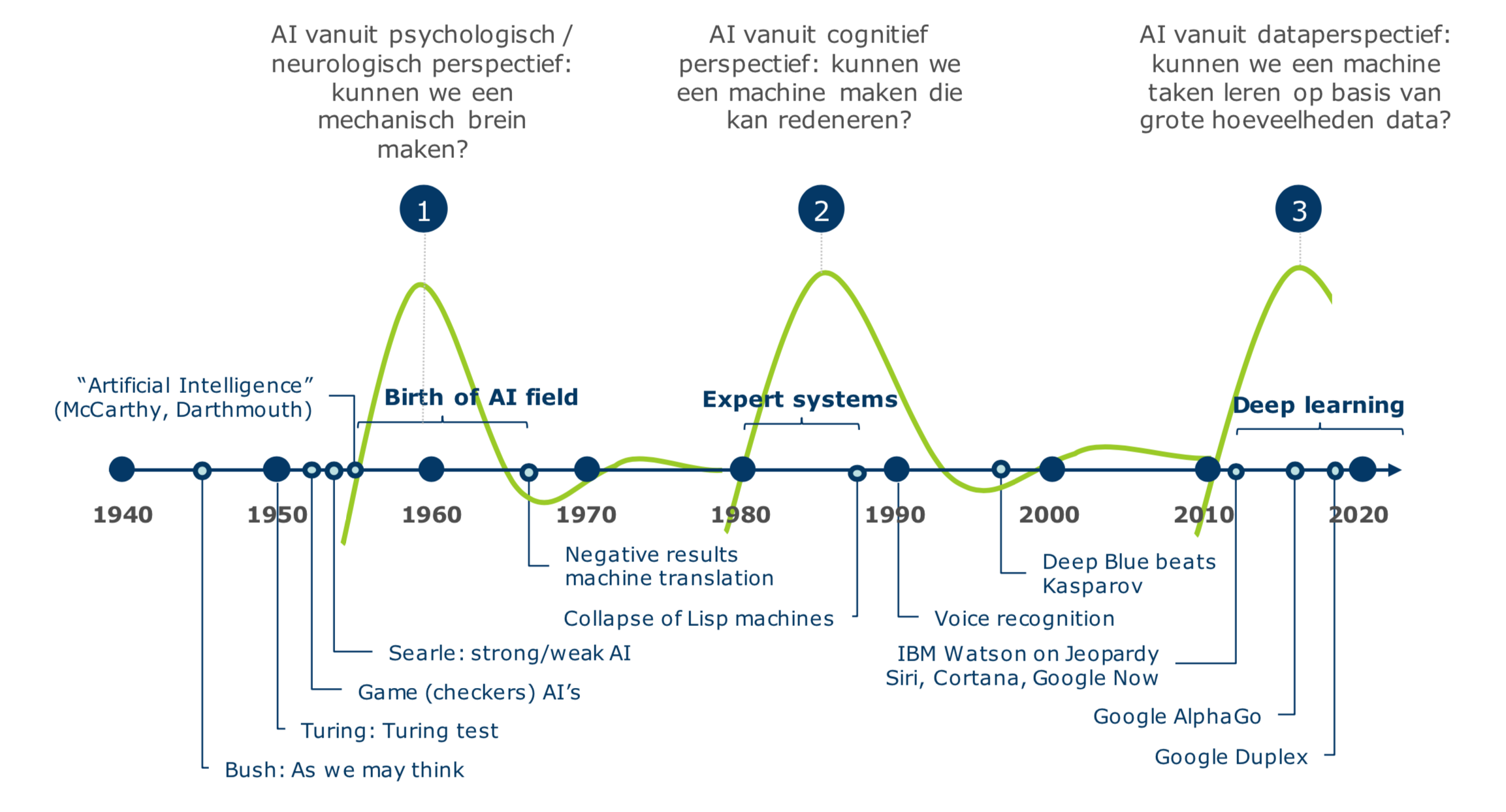

It is not easy to provide a single definition of AI, specifically when it comes to applications in education. Our research shows that especially when it comes to applications that (1) automate cognitive tasks and (2) use large amounts of data and data-driven methods, there are interesting, unresolved issues.

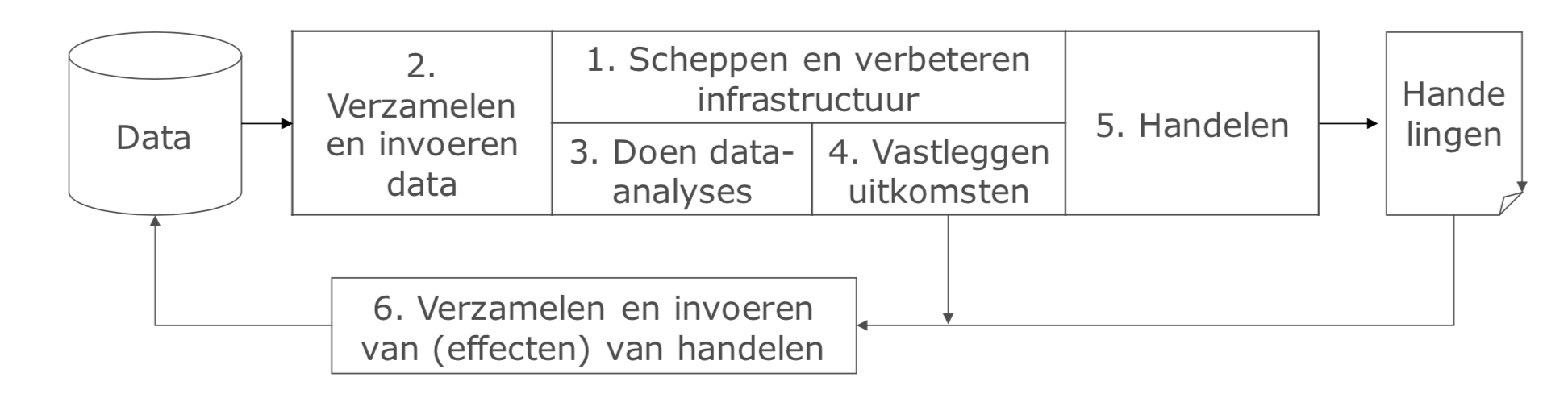

In the educational process teachers make decisions according to their own insight regarding (among other things) the method used, the teaching material, the way in which a student is approached, et cetera. Finally, teachers also make some formal decisions: what is the grade, and can a child move on to the next class? AIs can support teachers in various ways with these decisions. We distinguish four scenarios as most likely for the next 5-8 years: (1) an AI as a teaching assistant, (2) AI for learning analytics, (3) AI for personalization of education, and (4) AI for testing.

Can AI completely replace a teacher? Not in the near future.

At the point AI technology has become so smart that it can replace the teacher, it could in theory greatly improve education: after all, every student can be offered ‘tailor-made lessons’. This is however unlikely to happen any time soon: the expectation is that such artificial general intelligence (whereby an AI matches the level of intelligence of a person) will take at least a few more decades. However, this does not change the fact that less intelligent AI, which is already available today, can support the teacher in such a way that he or she can spend more time per student or work more efficiently.

What is allowed: what are the legal bottlenecks when applying AI in education?

The application of AI in education is affected by various generic regulations in the Netherlands. Some of these schemes are of supplementary law, which means that they can easily and often be deviated from for each contract, such as, for example, the Copyright Act and Database Law.

The flexibility of the private law regulations mentioned is much less found in the public law regulations, such as the rules on public access and the re-use of administrative and governmental information. The applicability of these schemes can prevent developers from entering into partnerships with institutions if this would mean that their knowledge would end up on the street. Additional contracts on intellectual rights can offer (partly) a helping hand here. Moreover, care must be taken to ensure that cooperation with market parties does not ultimately lead to the creation of dominant positions that may conflict with competition rules.

Decisions taken by institutions are of course fully governed by the general rules of administrative law, including the general principles of good administration. Applying these principles to AI applications can be tricky because they inherently clash with the black box that AI creates. Nevertheless, this does not seem to be an unsolvable problem.

The rules on the protection of personal data (Dutch AVG) may be a bottleneck. The nature of the personal data in education and the nature of AI go very poorly together (legally), and it seems very difficult to imagine that large-scale AI is permitted without legislation. This of course changes completely if the data to be used is no longer personal data.

If something goes wrong, there do not seem to be any significant problems in applying the rules on liability. This regime is very open and flexible so that those affected by AI applications do not have to be at risk.

The education-specific sectoral rules in themselves leave a great deal of freedom, and do not seem to contain any strict prohibitions. However, action must always be taken within the spirit and letter of the principles of educational law. In addition, the interests of the child will always have to be a central and ethical benchmark and the question will always be whether this is the case with AI.

In a more practical sense, sectoral regulations do present an obstacle: there is no strong arrangement for top-down steering on the content of education, apart from the fact that this is very sensitive. The movement from below is also a tricky one: initiatives may arise at individual institutions, but the polder model and the diversity of different regulations at the level of the institution are likely to stand in the way of a large-scale movement. This apart from the possible aversion of teachers (and institutions), whose interests and position can directly affect the application of AI.